Yes, believe it or not, slowness is a movement, in fact, it’s an institution.

The Philosophy of Slow Movement in Taoism

At the heart of Taoist practice lies the principle of wu wei, or non-action, which is not about inaction but about taking action that is in harmony with the natural flow of the universe. Slow movement embodies this principle, teaching us to move with deliberation and awareness, aligning our actions with the Tao, the fundamental nature of the universe.

Chee Soo, a revered figure in the world of Taoist arts, famously said, “The slowest is the fastest.” This paradoxical statement reveals a profound truth about the nature of learning and mastery in Taoist practices like Tai Chi. By adopting slow, deliberate movements, we engage deeply with the process, learning more efficiently and thoroughly. This deliberate pace allows for precision and acuity in learning, ensuring that movements are not just performed but are understood and internalized.

Furthermore, slow movement bridges the gap between the conscious and the unconscious mind. When we move slowly and with focus, we tap into our unconscious, enabling us to learn at a deeper level. This connection not only accelerates learning but also ensures that when rapid movement is necessary, it can be executed swiftly and effortlessly, unhindered by overthinking. This principle mirrors practices in music and other disciplines, where mastering slow, deliberate practice leads to the ability to perform complex actions at speed.

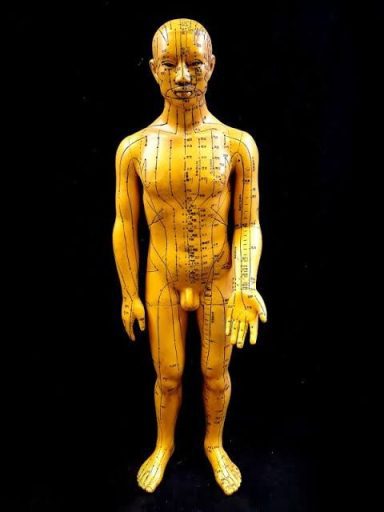

In the context of Tai Chi and Qigong, this focus on slow movement is not merely a physical exercise; it is a cultivation of qi, or life energy. Unlike concepts of muscle memory, which are rooted in physical repetition, the practice of Tai Chi emphasizes the flow and control of this vital energy. The movements, though outwardly slow, are internally vibrant, facilitating the circulation of qi throughout the body and promoting health, vitality, and a deep sense of inner balance.

This approach to movement and learning underscores the holistic nature of Taoist practices, where the journey of mastery involves the integration of body, mind, and spirit, moving beyond the physical to touch the essence of our being.

The Science and Benefits of Slow Movement

Delving into the realm of science, the benefits of slow movement, as practiced in Tai Chi and similar Taoist arts, find strong support in contemporary research. This body of evidence highlights the physical advantages and the profound mental and emotional impacts of engaging in slow, deliberate movements.

Slow movement practices have been shown to improve motor control by enhancing the neural pathways involved in movement coordination. This fine-tuning of motor skills is crucial not only for physical agility but also for preventing falls, especially in older adults. Furthermore, the emphasis on slow, controlled movements aids in developing a deep, intuitive understanding of one’s body, leading to improved posture and movement efficiency.

On a mental and emotional level, engaging in slow-movement practices encourages a state of focused awareness. This state, achieved by harmonizing movement with breath, has been linked to reduced stress levels and anxiety, promoting a sense of calm and well-being. Moreover, this focused state facilitates a meditative mindset, where the mind can achieve clarity and distractions are minimized. This clarity of mind is not only beneficial for mental health but also enhances cognitive function, including attention span and memory retention.

The practice of slow movement, therefore, acts as a bridge between the physical and the mental, offering a comprehensive approach to well-being. By encouraging the practitioner to move with intention and awareness, these practices cultivate an environment where the body can relax, the mind can clear, and the spirit can flourish. This holistic benefit package aligns perfectly with the Taoist view of health and harmony, emphasizing the importance of balance in all aspects of life.

Moreover, the internal focus on qi movement within these practices offers insights into the energetic dimensions of health. Unlike the purely physical perspective of exercise, slow movement in Taoism seeks to balance and enhance the flow of life energy throughout the body. This energetic approach provides a deeper level of healing and rejuvenation, addressing the symptoms of imbalance and the root causes, fostering a profound sense of vitality and inner peace.

Tai Chi: A Case Study in Slow Movement

Tai Chi, often described as meditation in motion, exemplifies the essence of slow movement within the Taoist tradition. As a martial art, it transcends the physicality of movement, embedding profound philosophical and energetic principles into each form and posture. Tai Chi’s practice vividly illustrates the adage “The slowest is the fastest,” showcasing how deliberate, mindful movements can lead to rapid internal growth and external proficiency.

The foundational practice of Tai Chi involves a series of movements performed with grace, precision, and fluidity, emphasizing the flow of qi, or life energy, throughout the body. This slow, intentional movement cultivates a deep connection between the mind, body, and spirit, allowing practitioners to achieve a state of inner stillness amidst motion. This paradoxical state of moving stillness is where the practitioner can access heightened levels of awareness and acuity, tapping into the deeper realms of consciousness and the unconscious.

One of the key benefits of Tai Chi as a slow-movement practice is its ability to improve physical health through strengthening the cardiovascular system, enhancing balance and flexibility, and reducing stress-related ailments. But beyond these tangible benefits, Tai Chi offers a pathway to spiritual enlightenment, embodying the Taoist pursuit of harmony between humanity and the natural world.

The practice of Tai Chi also illustrates that by slowing down, we can engage more fully with the present moment, allowing for a richer, more nuanced experience of life. In the context of learning and mastery, Tai Chi teaches that patience, persistence, and a focus on the journey rather than the destination are essential. This approach fosters the development of physical skills and the cultivation of virtues such as humility, respect, and compassion.

Furthermore, Tai Chi’s emphasis on the flow of qi highlights the distinction between the energetic focus of Taoist practices and the purely physical focus seen in many other forms of exercise. This energetic perspective offers insights into the interconnectedness of all life and the universe, providing a holistic approach to health and well-being that transcends physical boundaries.

Practical Applications of Slow Movement

Integrating slow movement principles into daily life offers a pathway to enhanced well-being accessible to everyone, regardless of age, fitness level, or background. The essence of these practices—whether through Tai Chi, Qigong, or simple mindful exercises—lies in their ability to foster a deeper connection with oneself and the surrounding world through deliberate, attentive movements.

Starting with Slow Movement Practices For those new to slow movement, the journey begins with recognising the value of slowing down. This can be as simple as dedicating a few moments each day to moving with intention and awareness, whether through performing daily tasks, walking, or engaging in specific exercises designed to cultivate mindfulness and presence.

Incorporating Tai Chi and Qigong into Your Routine Tai Chi and Qigong offer structured ways to practice slow movement, with routines that range from simple to complex, catering to all levels of experience. Beginners can start with basic Qigong breathing exercises and simple Tai Chi forms, gradually building up to more intricate sequences as their understanding and skill develop. These practices do not require special equipment or a large space, making them adaptable to most living environments.

Focusing on Breath and Movement Integration A key aspect of slow-movement practices is integrating breath with movement. This focus on breathing helps to regulate the flow of qi, or life energy, enhancing the health benefits of the exercises and promoting a state of calm and centeredness. By paying attention to the breath, practitioners can deepen their connection to their bodies and the present moment, elevating the practice from mere physical exercise to a holistic spiritual discipline.

Applying Slow Movement Principles to Everyday Life The slow movement principles can extend beyond formal practice into everyday activities. By adopting a mindful approach to daily tasks—paying attention to the sensations of movement, the rhythm of breath, and the quality of one’s attention—individuals can transform mundane activities into opportunities for presence and mindfulness. This approach not only enriches the quality of everyday life but also reinforces the practice of wu wei, acting effortlessly by the natural flow of life.

Challenges and Patience Embracing slow movement requires patience and persistence, especially in a world that often values speed and efficiency over depth and quality. The challenge for practitioners is to remain committed to the path, recognizing that the benefits of these practices unfold over time. This development’s gradual nature is a lesson in patience and trust in the process, reflecting the Taoist understanding that true growth and understanding emerge from a foundation of gentle, consistent effort.

In conclusion, the practical application of slow movement principles offers a profound way to enhance physical, mental, and spiritual well-being. By integrating these practices into daily life, individuals can discover a deeper sense of peace, balance, and harmony, embodying the Taoist ideal of living following the natural rhythms of the universe.

The World Institute of Slowness promotes a philosophy that advocates for slowing down life’s pace to enhance well-being, productivity, and happiness. It emphasizes a new way of thinking about time, aiming to make individuals healthier and more content by encouraging a slower approach to life’s activities. Their vision aligns with the benefits of slow-movement practices, suggesting that slowing down is beneficial and essential for a fulfilling life. For more detailed insights and to explore their initiatives, visit their website at https://www.theworldinstituteofslowness.com/.